Louisa May Alcott

1832 - 1888

Louisa May Alcott grew up in an unusual family, one that didn’t exactly fit with the general mid-19th century profile—a family that valued and encouraged girls’ creativity, emphasized progressive education, and was involved in all the major social causes of the day, including abolition, women’s rights, and vegetarianism. A family whose closest family friends were leading intellectuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, and a family that for a time lived on a vegan commune. For all that was going on around her, the two biggest influences on Louisa's life and writings were her father and her mother, though sometimes in conflicting ways.

Her father Bronson became a strict vegetarian after reading the works of Pythagoras, and that became the standard diet in the Alcott household. Unusual for his time, he was concerned not just about the various infirmities caused by eating meat, but also the suffering inflicted on animals, as well as the large amount of land needed to raise animals for food. Primarily because of Bronson’s ideals but also because the family struggled financially, the Alcott meals typically involved some mix of bread, porridge, potatoes, squash, apples, rice, graham meal, and water. Louisa was not as strict a vegetarian as her father, but she generally seems to have remained vegetarian most of her life. One of her relatives was William A. Alcott, who in 1850 co-founded and became the first president of the American Vegetarian Society, the first vegetarian organization in the US.

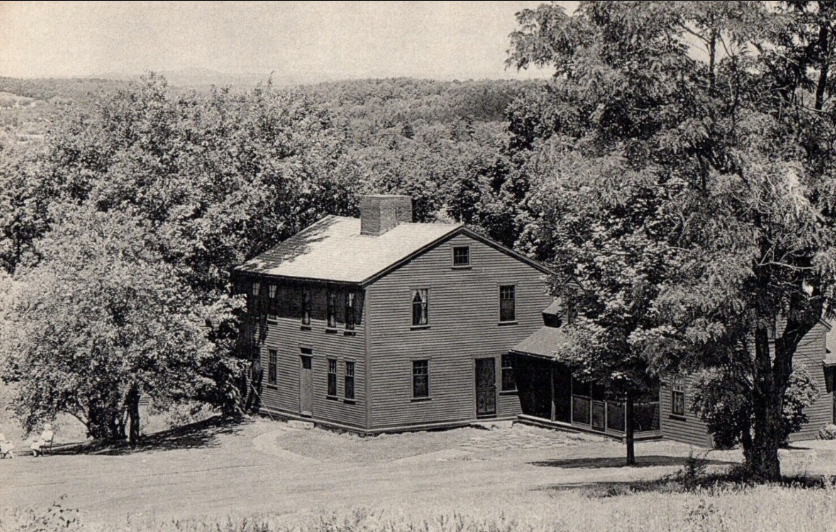

A major event in her life, which helped shape her overall outlook, was her father’s experiment in setting up a vegan commune called Fruitlands (the “Consociate Family at Fruitlands”) when Louisa was ten. The aim was “simplicity in diet, plain garments, pure bathing, unsullied dwellings, open conduct, gentle behavior, kindly sympathies, serene minds.” Yet their founding language might have foreshadowed that tough times could lie ahead: “We have not yet drawn out any preordained plan of daily operations... (But) by a faithful reliance on the spirit which actuates us, we are sure of attaining to clear revelations of daily practical duties... Where the Spirit of Love and Wisdom abounds, literal forms are needless, irksome, or hinderative.” Fruitlands lasted less than a year.

FRUITLANDS MUSEUM Harvard, Massachusetts

Louisa always admired her father and his idealism, but (like her mother Abigail) she balanced that with a sense of realism. Both at Fruitlands and in the Alcott house, while the men were busy with their philosophical thoughts, the women did the work. So Louisa became the main source of income for the family while still in her teens, both from doing a series of rather menial jobs but also from her writing. Yet she still remained positive despite the difficulties. As she wrote: “Far away there in the sunshine are my highest aspirations. I may not reach them, but I can look up and see their beauty, believe in them, and try to follow where they lead.”

Although Louisa never joined a Unitarian church, she made a point of listening to the sermons of several prominent Unitarian ministers, many of whom became friends. Louisa’s mother had a strong Unitarian background—including her brother being a minister—and through that side of the family Bronson explored Unitarianism. But he eventually moved away from it, concluding that “Preaching is too much an affair of another life—to teach men how to die rather than how to live.”

Throughout the ups and downs of her life, Louisa maintained an impressive sense of compassion for the poor, and perhaps her most central life principle was Emerson’s “Law of Compensation”—that doing good works for others brings happiness and satisfaction to your own life. In her later years, when she was financially secure from her books, had paid off all her family’s debts, and was increasingly experiencing painful illnesses, she took a trip to New York City. She saw some of the usual sights and attended various dinner parties in her honor, but was particularly interested in arranging visits to prisons and orphanages—visiting a brutal city prison, an insane asylum, a home for delinquent boys and girls, an inebriates home, and an asylum for abandoned, mentally ill children. After visiting that asylum, even though it was Christmas Day and she had skipped her traditional dinner, she wrote: “Yet it has been a very memorable day, and I feel as if I’d had a splendid feast seeing ... that every gift I put into their hands had come back to me in the ... delight of their unchild-like faces trying to smile.” For all her life accomplishments, Bronson and Abigail would have been most proud of that.

Sources: Louisa May Alcott: A Personal Biographer by Susan Cheever; Fruitlands quotes from letter published by A. Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane in the Herald of Freedom, September 8, 1843